Say NY Times and Star Bulletin: Navy should comply with Environmental Laws

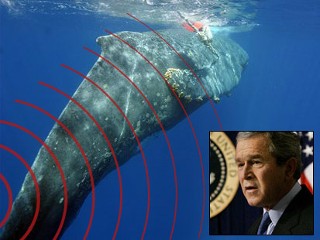

(graphic from abcnews.com)

The Supreme Court has taken up the question of whether the Bush Administration can exempt the Navy from laws protecting marine mammals from sonar, and media is chiming in. Both the New York Times and Star Bulletin have come out recently in favor of upholding environmental law when it comes to Navy training exercises.

From Op-Ed in today’s New York Times:

Environmentalists have long claimed that the Navy’s use of sonar for training exercises unduly threatens whales, dolphins and other acoustically sensitive marine creatures. The Navy has adopted some procedures to mitigate the risk but has resisted stronger protections ordered by two federal courts. The Supreme Court has now agreed to address the issue.

The justices will not try to determine the extent of harm but rather the balance of power between the executive branch and the courts in resolving such issues. In an effort to sidestep the courts, the Bush administration invoked national security to exempt the Navy from strict adherence to the two federal environmental laws that underlay the court decisions. The top court will now have to decide whether the military and the White House should be granted great deference when they declare that national security trumps environmental protection or whether the courts have a role in second-guessing military judgments and claims of fact.

The case at hand was filed by the Natural Resources Defense Council and other conservation groups to rein in Navy training exercises that use sonar to search for submarines off the coast of Southern California. The Navy says that its exercises pose little threat to marine life and that the training is vital to national security.

A federal district judge and a federal appeals court in California, after careful reviews of the facts, have found that the Navy’s arguments are largely hollow. Although the Navy likes to boast that there has never been a documented case of a whale death in 40 years of training, that may be mostly because no one has looked very hard. The Navy itself estimates that the current series of drills, conducted over two years, might permanently injure hundreds of whales and significantly disrupt the behavior of some 170,000 marine mammals.

No one has questioned that sonar training is vital to national security, and the federal courts have not tried to ban the training. They have simply tried to impose tough measures to minimize damage. The Navy objected to two proposed restrictions in particular — that it shut off its sonar when marine mammals are detected within 2,200 yards and power down its sonar under sea conditions that carry sound farther than normal.

High-ranking officers said these restrictions would cripple the Navy’s ability to train and certify strike groups as ready for combat. The appeals court, mining the Navy’s own reports of previous exercises, disagreed. It said the Navy, following earlier procedures, had already been shutting down sonars with little impact on training or certification.

It seems telling that the Navy has accepted the 2,200-yard safety zone for other sonar exercises. NATO requires the same zone, and the Australian Navy mandates a shutdown if a marine mammal is detected within 4,000 yards.

The federal courts have played a valuable role in deflating exaggerated claims of national security. Let us hope that the Supreme Court backs them up.

And, from our own Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

The Navy’s application for a new permit for sonar training exercises in Hawaii waters could be the last time it will need to go through the process, depending on a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court.

Should the court agree with the Bush administration’s assertion that it has the authority to override laws that protect the environment and marine mammals, the Navy would no longer be required to seek the permits designed to minimize harm to ocean species.

The court is not expected to focus on a continuing dispute between the Navy and environmental organizations about the level of injury sonar causes to marine mammals.

Instead, justices will decide whether the administration, with the support of the military, can set aside enforcement of well-established law. The administration argues that protective conditions put in place by federal courts jeopardize “the Navy’s ability to train sailors and marines for wartime deployment.”

The claim is belied by the fact that the Navy has been able to conduct training while mitigating harm.

The case involves naval exercises off the Southern California cast in which a federal judge restricted mid-frequency sonar use and required it to be shut down when a marine mammal is sighted within 6,000 feet. In a similar ruling in Hawaii, federal Judge David Ezra established several guidelines, putting the range at 5,000 feet. The different requirements have frustrated the Navy, but they are due to variations in coastal waters and marine mammal populations.

While the California case was proceeding through the appeals court, President Bush exempted the Navy from the Coastal Zone Management Act. At the same time, an executive branch agency, the Council on Environmental Quality, granted an exemption of the National Environmental Policy Act, claiming an emergency situation. The Defense Department has previously claimed an exception for “military readiness activity,” as allowed under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Through these laws, environmental groups have been successful in establishing restrictions, showing evidence that sonar soundings have injured or led to the deaths of whales. Navy studies have shown probable harm, disturbance or death to 175,000 marine mammals. The Navy also says only 37 whales have died from sonar since 1996, but that doesn’t mean that other haven’t been killed without their carcasses being found.

(Photo: 2006 dolphin stranding, Mozambique.)

The administration’s crafty argument, however, is aimed at defining the scope of executive authority, which might be a gamble because the court has not been sympathetic to Bush’s attempts to stretch presidential power.

A ruling will have implications in Hawaii, where the Navy’s permit for sonar exercises will expire in January. Until the court’s decision in its next term, the public has an opportunity to weigh in with the argument that training can be conducted effectively while reducing the risk of harm to animals in the sea.