Blog

News, updates, finds, stories, and tidbits from staff and community members at KAHEA. Got something to share? Email us at: kahea-alliance@hawaii.rr.com.

- The 2006 HIMB expedition on the NOAA vessel, Hi`ialakai, was one of the first major expeditions permitted in the newly established no-take state Refuge for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

- Despite a prohibition on the transport of live samples and the dumping of wastewater, state and federal officials noticed the researcher was transporting pieces of live coral over 100 miles across the multiple state and federal designated marine protected areas in an open-flow holding tank — a system that dumps used water from the tank back into the ocean.

- Official reports also allege she cultivated bacteria associated with coral disease while the ship traveled from Johnston Atoll.

- HIMB was not granted a permit to import coral or bacteria from Johnston Atoll to the Main Hawaiian Islands from the Agriculture Department. Nonetheless, the researcher was discovered to have bacteria samples from both NWHI and Johnston Atoll under cultivation on board the Hi`ialakai.

- The methods proposed by the HIMB disease researcher had also raised red flags in the scientific community. Before the vessel departed from Honolulu, scientific advisors reviewing the researchers proposal to import disease bacteria from Johnston Atoll to the Main Hawaiian Islands for the state Department of Agriculture noted “possible disastrous consequences” from the research methods, including the spread of potentially invasive coral species and coral disease.

- In their report, they discuss the “unclear scientific merit” of the research and found “little evident benefits from a conservation perspective.” They also expressed specific concerns about the proposed use of an “open flow” system for the transport of live samples and, instead, recommended that “all water in which the corals or microbes from them are held shall be kept in containers that do not release effluents into open or semi-open systems unless that water is sterilized or disinfected.”

Honolulu NWHI Hearing Online

Video of the Honolulu hearing on the Draft Management Plan for the Papahanaumokuakea Marine Monument in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands held in Honolulu on June 24th. The 1,200 page plan will direct the future of public trust resources in the last, large intact Hawaiian reef ecosystem in the world.

At the hearing, leading local conservation voices, including Keiko Bonk, Marjorie Ziegler, Dr. Stephanie Fried, Kyle Kajihiro, Leila Hubbard, Dave Raney, Don May and KAHEA staff (Evan, Bryna, Marti, and Miwa) testified to their concerns about the draft plan. (Testimony starts at 33:30).

In the largest no-take marine reserve on the planet, this draft of the Federal/State plan is proposing: the construction of a “small municipality” on Midway, new cruise ships, more tourists, increases in extractive research, new risks of invasive species introductions, exemptions for fishing, and opening of the area to bioprospecting. An expansion of military activities–including sonar, ballistic missile interceptions, and chemical warfare simulations–would be allowed to go forward with no mitigations. The plan also disbands the existing citizen advisory council, which is pretty much the only opportunity for members of the public (non-government scientists, advocates, cultural practitioners, and resource experts) to participate in decision-making.

You can also watch the hearings on `Olelo Channel 52.

You can support by submitting your own written comments, signing our petition, and spreading the word. Mahalo piha to the thousands who have already supported the call for a better plan!

WANTED: Critical Habitat for Monk Seal

KAHEA, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and the Ocean Conservancy, filed a formal petition yesterday, seeking to have beaches and surrounding waters on the main Hawaiian islands designated as critical habitat for Hawaiian monk seals under the Endangered Species Act.

Under the Endangered Species Act, critical habitat identifies geographic areas that contain features essential for the conservation of a threatened or endangered species and may require special management considerations.

Recent studies have shown that species with critical habitat are twice as likely to be recovering as species without it. Currently, the species has critical habitat designated only on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

The Hawaiian monk seal is one of the most endangered marine mammals in the world. Since the 1950s its population has dropped to about 1,300 animals and is continuing to decline. Scientists estimate populations will likely drop below 1,000 seals within a few years.

Monk seals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are dying of starvation, emaciated and weak, scientists have found. Pups have only about a one-in-five chance of surviving to adulthood. Other threats include drowning in abandoned fishing gear, shark predation, and disease.

Hawaiian monk seals are increasingly populating the main islands, where they are giving birth to healthy pups. For the past decade, the number of Hawaiian monk seal births has increased each year on the main islands, and the population of seals is growing steadily; the seals are in better condition than those in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. This indicates more food availability and a better chance of survival.

Global warming is also a threat to the survival of Hawaiian monk seals. Already, the conservation groups warn, important pupping beaches have been lost due to sea-level rise and erosion, and the northwestern islands will eventually disappear under predicted levels of sea-level rise since they are elevated only a few meters above sea level. The higher-elevation main islands are less vulnerable to sea-level rise.

Hawaiian monk seals are one of three species of monk seals. The Mediterranean monk seal is also critically endangered, while the Caribbean monk seal, which has not been seen in half a century, was declared extinct in June.

The Endangered Species Act requires that the government respond to this petition within 90 days.

Say NY Times and Star Bulletin: Navy should comply with Environmental Laws

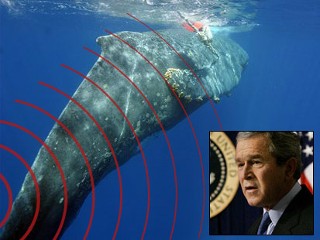

(graphic from abcnews.com)

The Supreme Court has taken up the question of whether the Bush Administration can exempt the Navy from laws protecting marine mammals from sonar, and media is chiming in. Both the New York Times and Star Bulletin have come out recently in favor of upholding environmental law when it comes to Navy training exercises.

From Op-Ed in today’s New York Times:

Environmentalists have long claimed that the Navy’s use of sonar for training exercises unduly threatens whales, dolphins and other acoustically sensitive marine creatures. The Navy has adopted some procedures to mitigate the risk but has resisted stronger protections ordered by two federal courts. The Supreme Court has now agreed to address the issue.

The justices will not try to determine the extent of harm but rather the balance of power between the executive branch and the courts in resolving such issues. In an effort to sidestep the courts, the Bush administration invoked national security to exempt the Navy from strict adherence to the two federal environmental laws that underlay the court decisions. The top court will now have to decide whether the military and the White House should be granted great deference when they declare that national security trumps environmental protection or whether the courts have a role in second-guessing military judgments and claims of fact.

The case at hand was filed by the Natural Resources Defense Council and other conservation groups to rein in Navy training exercises that use sonar to search for submarines off the coast of Southern California. The Navy says that its exercises pose little threat to marine life and that the training is vital to national security.

A federal district judge and a federal appeals court in California, after careful reviews of the facts, have found that the Navy’s arguments are largely hollow. Although the Navy likes to boast that there has never been a documented case of a whale death in 40 years of training, that may be mostly because no one has looked very hard. The Navy itself estimates that the current series of drills, conducted over two years, might permanently injure hundreds of whales and significantly disrupt the behavior of some 170,000 marine mammals.

No one has questioned that sonar training is vital to national security, and the federal courts have not tried to ban the training. They have simply tried to impose tough measures to minimize damage. The Navy objected to two proposed restrictions in particular — that it shut off its sonar when marine mammals are detected within 2,200 yards and power down its sonar under sea conditions that carry sound farther than normal.

High-ranking officers said these restrictions would cripple the Navy’s ability to train and certify strike groups as ready for combat. The appeals court, mining the Navy’s own reports of previous exercises, disagreed. It said the Navy, following earlier procedures, had already been shutting down sonars with little impact on training or certification.

It seems telling that the Navy has accepted the 2,200-yard safety zone for other sonar exercises. NATO requires the same zone, and the Australian Navy mandates a shutdown if a marine mammal is detected within 4,000 yards.

The federal courts have played a valuable role in deflating exaggerated claims of national security. Let us hope that the Supreme Court backs them up.

And, from our own Honolulu Star-Bulletin:

The Navy’s application for a new permit for sonar training exercises in Hawaii waters could be the last time it will need to go through the process, depending on a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court.

Should the court agree with the Bush administration’s assertion that it has the authority to override laws that protect the environment and marine mammals, the Navy would no longer be required to seek the permits designed to minimize harm to ocean species.

The court is not expected to focus on a continuing dispute between the Navy and environmental organizations about the level of injury sonar causes to marine mammals.

Instead, justices will decide whether the administration, with the support of the military, can set aside enforcement of well-established law. The administration argues that protective conditions put in place by federal courts jeopardize “the Navy’s ability to train sailors and marines for wartime deployment.”

The claim is belied by the fact that the Navy has been able to conduct training while mitigating harm.

The case involves naval exercises off the Southern California cast in which a federal judge restricted mid-frequency sonar use and required it to be shut down when a marine mammal is sighted within 6,000 feet. In a similar ruling in Hawaii, federal Judge David Ezra established several guidelines, putting the range at 5,000 feet. The different requirements have frustrated the Navy, but they are due to variations in coastal waters and marine mammal populations.

While the California case was proceeding through the appeals court, President Bush exempted the Navy from the Coastal Zone Management Act. At the same time, an executive branch agency, the Council on Environmental Quality, granted an exemption of the National Environmental Policy Act, claiming an emergency situation. The Defense Department has previously claimed an exception for “military readiness activity,” as allowed under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Through these laws, environmental groups have been successful in establishing restrictions, showing evidence that sonar soundings have injured or led to the deaths of whales. Navy studies have shown probable harm, disturbance or death to 175,000 marine mammals. The Navy also says only 37 whales have died from sonar since 1996, but that doesn’t mean that other haven’t been killed without their carcasses being found.

(Photo: 2006 dolphin stranding, Mozambique.)

The administration’s crafty argument, however, is aimed at defining the scope of executive authority, which might be a gamble because the court has not been sympathetic to Bush’s attempts to stretch presidential power.

A ruling will have implications in Hawaii, where the Navy’s permit for sonar exercises will expire in January. Until the court’s decision in its next term, the public has an opportunity to weigh in with the argument that training can be conducted effectively while reducing the risk of harm to animals in the sea.

Bombs Away! RIMPAC's Back

From Marti:

RIMPAC officially started on Sunday, meaning you can expect beach closures, random explosions, mass strandings, and displays of excessive military force throughout the month of July in Hawaii. Remember, RIMPAC is the bi-annual demonstration of U.S.-occupation that brought us the “Hanalei Bay Incident” in 2004, when 150 melonhead whales attempted to strand themselves because of the Navy’s use of high-intensity active sonar AND the unexplained nearshore explosion that shook the windows of Ewa Beach residents on Oahu in 2006.

This year we can look forward to 150 vessels and 20,000 troops from U.S.-backed militaries — like Russia, South Korea, Australia, Japan, and Peru — engaged in all kinds of wargames, such as assault landings, target practice with live rounds, and high-intensity active sonar.

To move forward with these (and all) exercises as originally outlined in the Navy’s giant range expansion plan, the Navy had to do *something* about the pesky limitations placed on those exercises by the State of Hawaii under the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA). This federal law was passed to encourage coastal states to do more to protect their precious coastal resources, including giving these states unique authority to require federal agencies abide by state coastal protections.

Under this unique federal law, the State of Hawaii said the Navy had to do two very reasonable things related to active sonar:

1. In nearshore waters, don’t let the active sonar go above 145 decibels because this is widely accepted (even by the Navy) to be a safe level for marine mammals and humans;

2. In all other situations, abide by the conditions required by Judge Erza in the Federal District Court.

It’s not just that the Navy said “No, we don’t have to follow your stinkin’ coastal protections,” but that the Navy enlisted other government attorneys to say “no” for them in a way that would have undermine all of the cooperative state-federal partnerships set up to protect U.S. coastal resources.

I say “would have” because the legal opinion the Navy ended up with is so poorly argued that it probably won’t have much affect. Of course, it will probably take more court action at some level to sort that out.

The two basic reasons why the Navy’s legal game of Twister fails is:

1. It relies on a court opinion that was vacated, meaning the judge revisited her decision and changed her mind based on new evidence or arguments.

2. The new argument that changed the judge’s mind was that the Endangered Species Act actually says states do, in fact, have the authority to protect endangered marine species to greater extent than the federal government. And it’s well accepted that the Endangered Species Act trumps the Marine Mammal Protection Act when it comes to endangered marine species.

Sigh.

We’ll continue to keep you updated on this saga. In the meantime, you can send your thanks to the State Planning and Director Abbey Mayer for standing up for coastal protections in Hawai`i nei.

Where's the public in this "public process"?

From Evan, law school student and Legal Fellow from the Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law working on staff with KAHEA this summer:

Was thrown into the deep waters of the 1,200 page Papahanaumokuakea Draft Monument Management Plan for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands this summer. It’s given me a unique opportunity to observe the workings of this “public” process. I’ve worked with experts in reviewing the plan, and attended several of the public hearings set up by the State/Federal Co-Trustee agencies. My observation: It is a recipe for disaster to take two years of closed door processes, package it into 4 very thick volumes and then expect the public at large to comment in any detail about what the plan entails.

(This is what 700 pages of the 1,200 page plan looks like. Erm, fun.)

I first attended the hearing at the Department of the Interior in Washington D.C. (the only hearing held outside our lovely archipelago). I was quickly made aware of the fact that I would be the only person offering public testimony. So much for the public in this public hearing.

After giving an impassioned 20 minute explanation of KAHEAʻs overarching concerns, I was flooded with a steady stream of “How do you do’s?” and “Can we get a copy of your testimony?” from interested national NGO’s and congressional staffers. I was glad for the opportunity to get the word out on our key concerns, despite the dismal showing of public engagement.

The next chance I had to attend was the final night of the Federal/State Co-Trustee Island Summer Hearings Tour 2008. From all accounts, the crowd of about 60 at the Japanese Cultural Center in Moilili was by far the largest of any of the meetings. The format was a little different from D.C. and to be honest, quite unlike anything I had ever witnessed before. After a formal introduction to the Monument (same as D.C.), was an open discussion with Monument staff who were broken into 6 tables that synchronized with 6 priority management needs from the plan. It had an element of “spoon-feeding” to it, and considering that many had come to supply public testimony, made things run a little later than they may have otherwise. Nonetheless, I found this segue to be a nice opportunity to bring some of my major gripes with the plan directly to the folks who had put it together.

Over the course of this experience, I have been amazed at the bizarre nature of this top-down “public” process.

When asked: “Why was the citizen’s advisory council removed from the plan?”

A rep responded: “Actually, we do want one. We left it out because we wanted to see what the public would come up with during the review period.”

I’d suggest that a proper, engaged public process wouldn’t have waited until the review period to see what the “the public would come up with.” It all reminded me of the hide the ball game my law professors sometimes like to play. Except this is not law school. Why intentionally leave something as important as public oversight and advisory committees out of the plan, on purpose? Something as important as the Monument surely deserves better!

All told, the nine public meetings yielded about 250 total attendees and 70 testifiers. Not exactly up to par with the 100,000+ comments that helped create the Monument. Essentially, there was very little public at in these public meetings.

It is the job of the government managers to engage the public in this process–to bring the place and the process to the people. The length of time since the Co-Trustees have seen daylight, coupled with the sheer magnitude of the plan are likely culprits for this erosion of public engagement. I simply cannot accept that after previous outpourings of energy, suddenly nobody cares enough about this place to speak out. Another likely reality involves the seventy five day open period for submitting comments, which is rapidly coming to a close on July 8th. Compared to the two years it took countless full time staff to develop the plan, 75 days is simply too short a time to garner the effective and real public involvement needed to protect this special place.

This is one of the truly intact Hawaiian reef ecosystems left on earth–precious cultural and natural heritage that deserves our attention and voices. You can learn more about problems with the current plan, and how to ask for a better process and more time to get the “public” involved at: www.kahea.org.

conservation plan = more impacts? we don't get it.

A short video we put together on the new draft of a 15-year plan for the future of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.* We’ve read all 1,200 pages of it, and reviewed it with experts everywhere from Sierra Club to Environmental Defense. Our conclusion? We can do much, much better.

Now, we’re seeking signatures on a petition asking for a better, stronger Plan for this fragile wahi pana.

The current draft is a plan for conservation which, inexplicably, actually expands the footprint of human activity in this pristine and uniquely Hawaiian coral reef ecosystem.

In the largest no-take marine reserve on the planet, this draft of the Federal/State plan is proposing the construction of a “small municipality” on Midway, new cruise ships, more tourists, increases in extractive research, new risks of invasive species introductions, exemptions for fishing, and opening of the area to bioprospecting. An expansion of military activities–including sonar, ballistic missile interceptions, and chemical warfare simulations–would be allowed to go forward with no mitigations. The plan also disbands the existing citizen advisory council, which is pretty much the only opportunity for members of the public (non-government scientists, advocates, cultural practitioners, and resource experts) to participate in decision-making. Yeesh.

Over 100,000 people from all over the world helped establish the Papahanaumokuakea National Marine Monument and the Hawaii State NWHI Refuge–perhaps the most visionary legal marine area protections in history. We need to ask government managers for a plan which upholds these strong protections. We should be working towards full conservation, NOT creating and formalizing exceptions to the rules. That’s our position, anyway.

If you agree, please take a few seconds to add your name to the petition. This last intact, endangered and uniquely Hawaiian coral reef ecosystem deserves a plan for its FULL conservation. Unless we show broad public support, protections we fought so hard for will be paper, not practice.

*The hearings mentioned in the video are over, but there is still one week left to make your voice heard. More information at www.kahea.org. Deadline is July 8, 2008.

It's about respect, man.

From Miwa:

It’s true that the HIMB researcher currently under investigation for NWHI permit violations is coral disease researcher, and that coral disease is bad stuff. In doing this work, we’ve learned more about coral disease than we probably ever wanted to–coral disease is an important concern in our oceans worldwide.

So why advocate strict enforcement for a coral disease researcher?

What’s important to understand is that: It’s not just about understanding the ecosystem and its resources.

It is about achieving that understanding in a pono way–by researchers who respect the cultural and natural significance of the resource, take responsibility for their actions, and are committed to following the rules put in place to protect this fragile and uniquely Hawaiian place.

And so you have to ask: was this research done in a pono way?

We’re not the only ones for whom this stuff seemed just a little, er, inappropriate.

I come from a conservation and research background–and I admit that makes me feel a bit squirmy when the human footprint being talked about hits so close to home. This is a true test for all of us–for conservation and science communities–to recognize the scope of impact of our own activities. For a place as fragile, and as culturally and ecologically unique as the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, this means taking a hard look at our attitudes, our institutions, our intentions, and our ambitions.

In the end, it’s really all about respect. It’s either there, or it’s not. Respect for rules, respect for the resource, and respect for the concerned public to whom this public trust resource ultimately belongs.

In her testimony to the BLNR on July 27, 2007, the HIMB researcher under investigation defended her actions, characterizing the violations as a “minor misunderstanding.”

“There was never any risk to the environment for what I did, whether it was approved or not,” she testified.

For the largest conservation area of its kind in the world, for the people who fought so hard for the rules protecting this incredible and untouched Hawaiian place, for all the future generations of Hawaiian people to whom this place also belongs… I have to believe that we can do better.

(top picture from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/5084944.stm, bottom from kahea.org)